ESSENTIAL QUESTION

How and why does President Abraham Lincoln tie the Battle of Gettysburg to the American Revolution?

CONTEXT

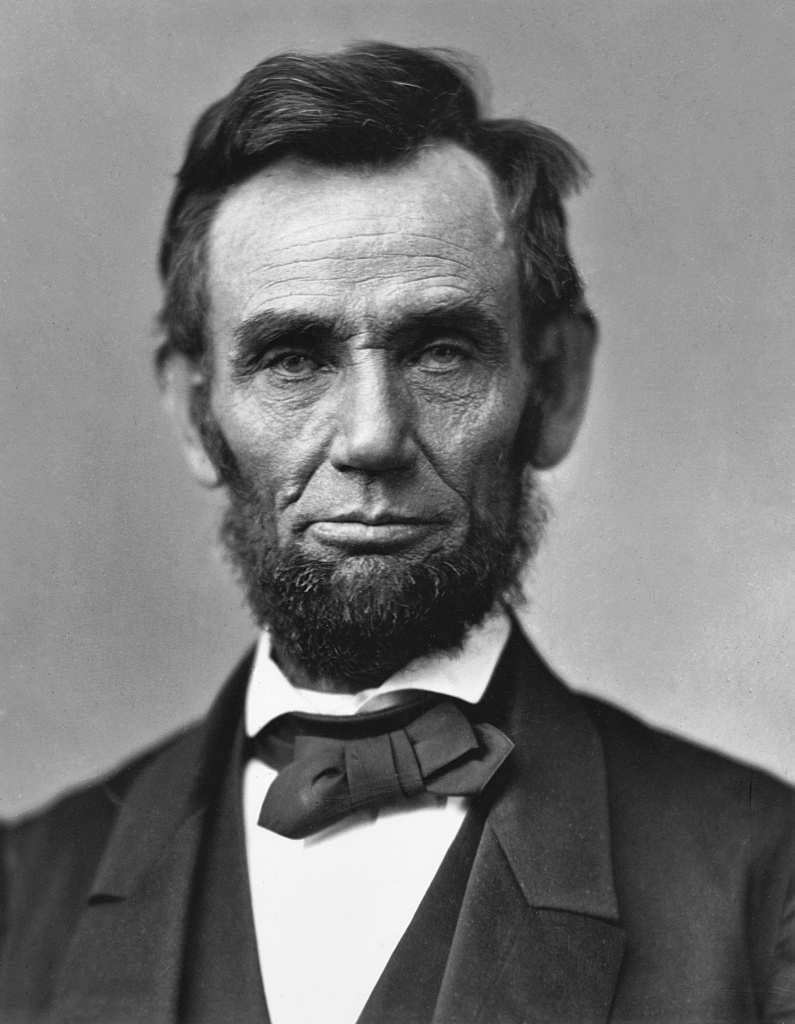

It was a short speech. Only 10 sentences. It was over so fast, photographers did not get a chance to capture an image of the President speaking at the site of the carnage–fifty thousand dead, wounded, or missing–that was the battle of Gettysburg (July 1-3, 1863). The battle was seen as a Union victory, and yet both the Confederate and Union generals-in-chief offered their resignations after the battle (neither of which was accepted). After a Commission was established to organize proper burials, it was felt that a dramatic oration, common at the time, was necessary, and the Commission’s choice was Edward Everett, a well-loved orator who had spoken at other battlefields, including Bunker Hill. Everett agreed to be the speaker at the dedication of this new national cemetery, and later federal officials, including President Lincoln, were invited to join the Commission’s program. But Everett would be the headliner–Lincoln’s short address would follow. After Everett’s two hour speech on November 19, 1863, in front of approximately 20,000 spectators, Lincoln rose and spoke for three minutes.

TEXT

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation or any nation so conceived and so dedicated can long endure. We are met on a great battlefield of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we cannot dedicate–we cannot consecrate–we cannot hallow–this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here have consecrated it far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us, the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so noble advanced.

It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us–that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion; that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain; that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom; and that government of the people, but the people, fore the people shall not perish from the earth.

INQUIRY

- Lincoln does not specifically mention specific military units, slavery, Gettysburg, or Pennsylvania. Why do you believe he focused more on generalities? What was the effect?

- What is the difference between describing an event and interpreting an event?

- What does Lincoln mean by “a new birth of freedom”?

- An allusion is an expression designed to call something to mind without specifically saying it. In what ways does Lincoln allude to the American Revolution? What is the effect?

- What is the tone (Lincoln’s attitude toward the subject) of this speech? How does Lincoln create that tone? What does he ask his audience to do?

- What is the mood (the attitude Lincoln wishes to create in his audience) of this speech? How does Lincoln create that mood? In what ways are the tone and mood of this speech related?

- To whom is Lincoln addressing the speech–the Union, the Confederacy, or both? Defend your answer.

- How and why does Lincoln connect Gettysburg to the American Revolution?

- Although Lincoln says that “the world will little note nor long remember what we say here…” and yet we do remember the words. Why do you believe these words have endured?

- In what ways can the past influence our lives today?

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Wills, Gary. Lincoln at Gettysburg The Words that Remade America. 1992. Copyright Literary Research, Inc.